Schulmädchen-Report 2017 AD

orinid’s regulation dirndl offered scant protection from the museum’s brutal climate control vents. Fearing pneumonia, she hugged herself in transit. Arrows etched in tiny brass plaques teased her through bust-choked galleries toward her assigned topic: the all-organic reliquary exhibit. On display were remains of carnivorous arthropods with petrified bellies rumored to house morsels of the canonized.

But as the canon in question derived only from the local hillside animists (known for their vigorous looting of Christian iconography), Dorinid esteemed the beasts over the victims. Surely the now-calcified tree hoach (Discerpula pruinosa, north wall, far left) exuded more grace than cretinous St. Ottoken — who, seeking to learn the animal’s language, became intimate with a drove of specimens, nourishing them steadily with his own blood until they progressed to his flesh. She pictured him addressing the Deity through His avatars in his final minutes, then wondered what portion this particular hoach had relished.

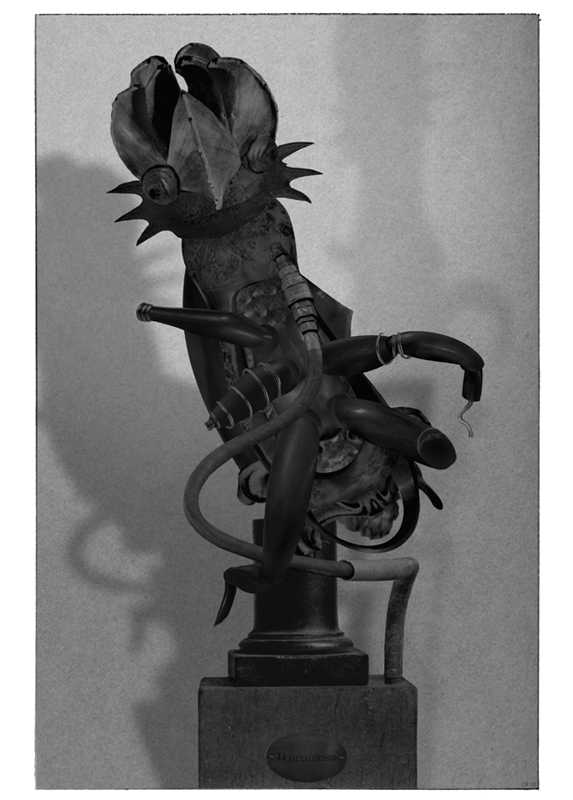

And how did the faithful interpret the chance munching of one of these blessed receptacles by another? For the long-extinct labyrrha grub (Daedalos iricundus, right of hoach), with its buccal funnel intact and gullet agape, looked ready even now to broach ontological quandaries via arbitrary snacking. Though inert, its rudely dilated head was poised to rasp a gash in the ocher proto-buttocks of the equally ravenous Xanthopolyptus elegans propped nearby. The whole room in fact bristled with such postures, recalling a base order incongruous with humanoid faith.

Dorinid wavered for a moment, pondering the divine repercussions of a rift in the food chain. A frayed diagram offered data from the distant west wall. She started toward it, but lost momentum as she steered her cold flesh around the fossils.

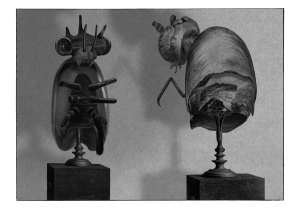

Shivering yet drowsy, she paused between the king saliva lubber (Ovula asperginis) and the foghorned ippollolus nymph (Hyperculex adulescens). Both stood upright but stooped at roughly the same level, as though supporting an invisible beam. This contextualized them as human artifacts, more so than the other fixtures — and this, in its quaint profanity, stole the focus from her studies. Remembrance gripped her basal ganglia and lugged her back ten years to an event that she could recall but not interpret.

It must have been a dream, despite the injuries. It transpired in the pitch-black middle of night, when her parents, not uttering a word, swiped her from bed, wrapped her in dark pelts, and drove her for miles to some desolate neighborhood where the lighting was poor and a thin, stagnant mist hung close to the ground. They placed her before a pair of statues on plinths — not readymade totems like today’s relics, but carved wooden animals with human limbs and traditional grimaces. The figure holding a bow and a quiver had a boar’s face, and the other one, with a spear, must have been a hare. She recognized them as characters from a fable she’d come across in a book. She couldn’t remember the story offhand — only that they were bitter enemies, and that neither had a legitimate grievance. Chiseled beneath each pedestal was a list of crimes committed by the subject, of which many, such as burglary and rape, had no bearing on the original story — which little Dorinid tried hard to recall — and when, finally, she identified the fable, a black curtain dropped over her eyes and she fell hard against the cold pavement and split open her chin —

— Just as the adolescent Dorinid now lost consciousness in this frigid gallery (the A/C must have been malfunctioning) and collapsed, her last waking thought being that her temperature was surely below -0.56 °C (though it wasn’t) and thus her frozen body would shatter like a wineglass against the old marble floor — when in fact all that broke was her jaw, albeit in seven fragments, resulting in extensive surgery and months of painful recuperation.